In 2018, Matthew de Brecht showed that a co-analytic subset of a quasi-Polish space is either quasi-Polish or else contains a countable Π02 subset homeomorphic to one of the following four spaces:

- S0, a space I have already talked about in the January 2023 post, and which is a countably branching tree with countable branches extending from top to bottom;

- S1, which is simply N with the cofinite topology;

- S2, which is simply the space Q of rational numbers;

- SD, which is N with the Alexandroff topology of its ordering.

The names that de Brecht chose are meant to match their separation properties: S0 is T0, but nothing more, S1 is T1, S2 is T2, and SD is TD. Don’t worry about “co-analytic” or “Π02” for now. The point is essentially to characterize quasi-Polishness by excluding just 4 specific subspaces.

I have long planned to explain how this works, but this is pretty technical and long. However, there is something simpler I can explain. In [1, Theorem 4.3], de Brecht proved that a second-countable T0 space is sober if and only if it does not contain a Π02 subspace homeomorphic to S1 or of SD. The proof involves looking at perfect subspaces, TD subspaces, and so on. This result was improved upon by Qingguo Li, Mengjie Jin, Hualin Miao, and Shong Chen [2, Section 3], who showed that first-countability was enough, instead of second-countability. Then Hualin Miao, Xiaodong Jia, Ao Shen and Qingguo Li showed that one can characterize those T0 spaces that are not ω-well-filtered as those that do not contain either S1 or SD as Skula-closed subspaces [3]. All that is based on de Brecht’s results and techniques, but seems easier to explain… unless you realize that the proof use some of de Brecht’s technical lemmas.

While the proofs I will give start out by following the same path as in [2], I will then fork and use more elementary (you won’t need to learn any auxiliary theorems, I will state everything that you need) and hopefully simpler arguments, although we will need to talk about Skula-closed subspaces and then ω-Rudin sets at some point, and this will start being complex again.

ω-well-filtered spaces

A space X is well-filtered if and only if given any filtered family (Qi)i ∈ I of compact saturated subsets whose intersection is included in some open subset U, some Qi is already included in U. Every sober space is well-filtered (Proposition 8.3.5 in the book).

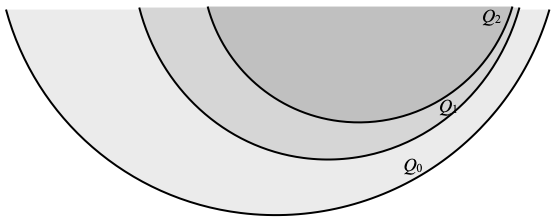

A refinement of this is ω-well-filtered spaces, see the October 2019 post: X is ω-well-filtered if and only if given any descending sequence Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … of compact saturated subsets whose intersection is included in some open subset U, some Qn is already included in U.

In the list of spaces I have given at the beginning of this post:

- S0 is sober (see the January 2023 post), hence it is well-filtered, and in particular an ω-well-filtered space.

- The space S2 is Hausdorff (or T2), and every Hausdorff space is sober (Proposition 8.2.12 in the book), hence well-filtered, hence ω-well-filtered space.

- The space S1, which is just N with the cofinite topology, is not ω-well-filtered.

Here is why. In the cofinite topology, the proper closed subsets are the finite subsets, so every descending sequence of closed sets stabilizes; by taking complements, ascending sequences of open sets stabilize, so S1 is a Noetherian space (Proposition 9.7.6 in the book). In a Noetherian space, every subspace is compact.

In S1, which is T1, therefore, every subset is even compact saturated. We let Qn ≝ {n, n+1, …} for each n ∈ N, and those are therefore vacuously compact saturated. We let U be empty: ∩n ∈ N Qn is empty, hence included in U, but no Qn is included in U.

Therefore S1 is not ω-well-filtered. - The space SD, which is just N with the Alexandroff topology of its usual ordering ≤, namely whose open subsets are the empty set and the sets ↑n = {n, n+1, …}, is not ω-well-filtered.

Indeed, Qn ≝ ↑n is just open, but also compact saturated, and as above, taking U to be empty leads to a case where ∩n ∈ N Qn ⊆ U but no Qn is included in U.

What must happen in a non-ω-well-filtered space

In the following, we consider a non-ω-well-filtered T0 space X, and we will see what emerges—in short, we will find homeomorphic copies of S1 or of SD sitting as subspaces of X. Later on, we will see that they must be Skula-closed, too.

By definition of ω-well-filteredness, there is a descending sequence Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … of compact saturated subsets of X and there is an open subset U of X such that ∩n ∈ N Qn ⊆ U but: (*) no Qn is included in U.

We fix the sequence Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … but will make U vary. The collection F of open sets U satisfying property (*) is a non-empty dcpo under inclusion. Indeed, it is non-empty by assumption. In order to show that F is a dcpo, we consider an arbitrary directed family (Ui)i ∈ I of open subsets of X that satisfy property (*). If some Qn were included in ∪i ∈ I Ui, then it would be included in some Ui, since Qn is compact (see Proposition 4.4.7 in the book), and that is impossible since Ui satisfies property (*). Hence ∪i ∈ I Ui is in F, and F is a dcpo.

In particular, F is an inductive poset. By Zorn’s Lemma (Theorem 2.4.2 in the book), it has a maximal element U0 above any chosen element U. By assumption, we can choose that element U so that not only property (*) is satisfied, but also ∩n ∈ N Qn ⊆ U. Hence also ∩n ∈ N Qn ⊆ U0.

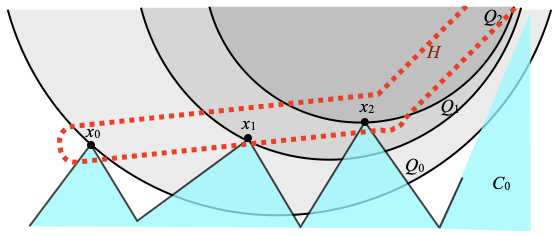

Let C0 be the complement of U0 in X. C0 is a closed set. By definition, C0 is a minimal closed set that intersects every Qn (rephrasing property (*)), while ∩n ∈ N Qn does not intersect C0. Since C0 intersects every Qn, we can pick an element xn that is both in C0 and in Qn for each n ∈ N. Hence here is what our working assumption—that X is not ω-well-filtered space—boils down to.

Setting. X is a non-ω-well-filtered T0 space, Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … is a decreasing sequence of compact saturated subsets of X, C0 is a minimal closed set that intersects every Qn, while ∩n ∈ N Qn does not intersect C0, and xn ∈ C0 ⋂ Qn for every n ∈ N. We also let H ≝ {xn | n ∈ N}.

We equip C0 and H with the subspace topology induced from the inclusion in X. The following Lemmas A and B are part of the proof of Lemma 3.2 in [3].

Lemma A. In the Setting, C0 is equal to the closure cl (H) and H is infinite.

Proof. The closure cl (H) of H is closed, included in C0, and intersects every Qn (at xn). By minimality of C0, it must be equal to C0.

Let us assume that H is finite. Since ∩n ∈ N Qn does not intersect C0, hence does not intersect H either, every point y of H is outside Qny for some ny ∈ N. Taking n larger than every index ny, which is possible since H is finite, H is disjoint from Qn; and this is impossible, since xn is in both. Therefore H is infinite. ☐

Lemma B. In the Setting, every proper closed subset of C0 intersets H at only finitely many points.

Proof. Let C be a closed subset of C0 such that C ∩ H is infinite. We will show that C must be equal to the whole of C0, contradicting the fact that it is a proper subset of C0. Since C ∩ H is infinite, there are infinitely many indices n ∈ N such that xn is in C. Then C intersects Qn, and because Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn, C must intersect Q0, Q1, …, Qn; and this for infinitely many values of n, hence for n arbitrarily large. It follows that C intersects every Qn. By minimality of C0, we must have C = C0. ☐

As a subspace of X, H has a specialization preordering, which happens to be the restriction of the specialization ordering ≤ on X (Proposition 4.9.5 in the book). We continue to write it as ≤.

Lemma C. In the Setting, if there is a point of H that is not below any maximal point of H, then H has a subspace H’ that is homeomorphic to SD and such that cl (H’) = C0.

Proof. Let xn0 be a point of H that is not below any maximal point of H. There must be another point xn1 of H such that xn0 < xn1, otherwise xn0 itself would be maximal. Also, xn1 is not below any maximal point of H: if xn1 were below some maximal point y, then xn0 would be, too. Proceeding with xn1 as we did with xn0, there is another point xn2 of H such that xn1 < xn2 and xn2 is below no maximal point of H, and so on.

Let H’ be {xn0, xn1, …, xnk, …} and C’ be its closure in X. Then C’ is included in C0, is closed in C0, and its intersection with H contains H’, which is infinite. Using Lemma B, C’ cannot be a proper subset of C0, so C’ = C0. In other words, cl (H’) = C0.

The important point is that there is a unique topology on H’ that has ≤ as its specialization ordering. This is proved as follows. For every open subset V of H’ in the Alexandroff topology of ≤, i.e., for every upwards-closed subset V of H’, V is either empty or has a unique least element y, because H’ is well-founded. If V is empty, then it is open in any topology. Otherwise, V = ↑y. If y is the least element xn0 of H’, then V is the whole of H’, which is also open in any topology. Otherwise, y = xnk+1 for some k ∈ N, and then V is the complement of ↓xnk; therefore V is open in the upper topology, which is the topology generated by the complements of downward closures of points. It follows that the Alexandroff topology is coarser than the upper topology. It is also finer, trivially, so the two topologies coincide. We conclude by Exercise 4.2.14 in the book, which states that on a preordered set, there is a unique topology that has the given preordering as its specialization preordering if and only if the Alexandroff and upper topologies coincide.

This entails that the topology of H’ is the Alexandroff topology of ≤ (also its upper topology, and also its Scott topology, etc., but that does not matter at this point).

The map f : k ↦ xnk is a strictly monotonic bijection of N onto H’, by construction. (By strictly monotonic, we mean that k<k’ implies f(k)<f(k’).) Hence its inverse is also strictly monotonic. We remember that SD is simply N, with the Alexandroff topology of its ordering ≤. A function between posets is monotonic if and only if it is continuous with respect to the corresponding Alexandroff topologies (Exercise 4.3.10 in the book), so f is a homeomorphism. ☐

Lemma D. In the Setting, and if every point of H is below some maximal point, then H has a subspace H’ that is homeomorphic to S1 and such that cl (H’) = C0.

Proof. Let Max H be the subset of maximal points of H. The assumption that every point of H is below some maximal point is equivalent to the fact that H is equal to the downward closure of Max H in H, namely to ↓Max H ⋂ H.

For every point y of Max H, ↓y is included in C0, and is closed. It cannot be that ↓y = C0: otherwise y would be equal to every xn, hence would be in every Qn, and it would also be in C0, contradicting the fact that ∩n ∈ N Qn and C0 are disjoint (see Setting). Hence ↓y is a proper closed subset of C0, and therefore contains only finitely many points of H by Lemma B.

If Max H were finite, then H = ↓Max H ⋂ H would be equal to the union of the finite sets ↓y ⋂ H over the finitely many elements y of Max H, hence would be finite. This directly contradicts Lemma A: so Max H is infinite. It is also countable, because it is included in the countable set H, so there is a bijection f : N → Max H.

Every closed subset of Max H is of the form C ∩ Max H for some closed subset C of X. Replacing C by C ∩ C0, we may assume that C is included in C0, and is then a closed subset of C0, seen as a subspace. By Lemma C, either C = C0 or C contains only finitely many points in H. In other words, every closed subset of Max H is either the whole of Max H or is finite, or equivalently, every closed subset of Max H is closed in the cofinite topology on Max H.

Conversely, let us consider an arbitrary subset C’ of Max H that is closed in the cofinite topology. We claim that C’ is closed in the subspace topology induced by the inclusion in C0 (or X).

- If C’ = Max H, then C’ is closed in Max H in the subspace topology.

- Otherwise, C’ is finite. Let C ≝ ↓C’. Being the downward closure of a finite set, C is closed in X (see Exercise 4.2.8 in the book).

We claim that C’ = C ∩ Max H. That C’ ⊆ C ∩ Max H is clear. In the reverse direction, every point x of C ∩ Max H is below some point y of C’ ⊆ Max H; but since x and y are both maximal in H and x≤y, we must have x=y. (This is where we use the fact that X is T0.) Then x is in C’, because y is.

The equality C’ = C ∩ Max H shows that C’ is closed in Max H with the subspace topology.

We let H’ ≝ Max H. We have just proved that the subspace topology on H’ is the cofinite topology. Hence f is a homeomorphism from N with its own cofinite topology—namely, S1—onto H’. ☐

Putting together Lemmas C and D, in the Setting, there is a homeomorphic copy H’ of S1 or of SD that sits as a subspace of the non-ω-well-filtered space X. Additionally, cl(H’) is equal to the minimal closed set C0 intersecting every Qn but not ∩n ∈ N Qn, which we chose initially.

This is not yet a characterization of ω-well-filtered spaces, and we need to go through Skula-closed subsets, as Miao, Jia, Shen and Li do [3].

Skula-closed subsets

I have already talked about the Skula topology several times, and notably in the August 2019 post, where we showed that for a subspace X of a sober space Z, it is equivalent for X to be sober, or to be Skula-closed. This is also mentioned in Exercise 9.7.16 of the book.

Here is a quick reminder of the definition. The Skula topology (also called the strong topology) on a topological space X is the topology generated by the open subsets and the closed subsets of X. It is equivalent to define it as the topology generated by the open subsets and the downwards-closed subsets of X. A Skula-closed subset of X is one that is closed in the Skula topology; Skula-open is defined similarly.

Lemma E. In the Setting, any countably infinite subset A of C0 such that cl (A) = C0 is Skula-closed in X. In particular, H is Skula-closed in X, and the subspaces H’ found in Lemma C or in Lemma D are Skula-closed in X.

Proof. Both H and H’ (whether built in Lemma C or in Lemma D) are countably infinite subsets of C0 and their closure is equal to C0, by Lemma A, C or D respectively. Hence it suffices to prove the first part of the lemma.

The argument is similar to one used in the proof of Lemma 3.2 of [3], except the authors write B for our H’, and Hn for what is essentially our forthcoming An. We write A as {y0, y1, …, yn, …}, where the points yn are pairwise distinct. For every n ∈ N, we let An ≝ {y0, y1, …, yn} ∪ Qn.

Since every downwards-closed subset of X is Skula-open, by taking complements we obtain that every upwards-closed subset of X is Skula-closed. In particular, Qn is Skula-closed. Every one-point set {x} is Skula-closed, because it arises as the intersection of the closed set ↓x with the upwards-closed (hence Skula-closed) set ↑x, using the fact that X is T0. For every n ∈ N, An is a finite union of Skula-closed sets, and is therefore Skula-closed.

We claim that A = (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0.

- Every point of A is equal to ym for some m ∈ N. We verify that ym ∈ (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0. By definition of ym, ym is in A, hence in C0, and it remains to verify that ym ∈ An for every n ∈ N. If m≤n, then ym ∈ {y0, y1, …, yn} ⊆ An. Otherwise, ym is in Qm, which is included in Qn, hence in An.

Therefore A ⊆ (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0. - In the reverse direction, let y be a point of (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0. We reason by contradiction and we assume that y is not in A. This means that y is not equal to any point y0, y1, …, yn, … For every n ∈ N, y is in An = {y0, y1, …, yn} ∪ Qn, and therefore must be in Qn. Hence y is in ∩n ∈ N Qn. But ∩n ∈ N Qn does not intersect C0, while y lies in C0: contradiction.

Therefore (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0 ⊆ A.

The formula A = (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0 displays A as an intersection of Skula-closed subsets of X, so A is Skula-closed. ☐

Putting together what we now know from Lemmas C, D and E, if X is not ω-well-filtered and T0, then there is a homeomorphic copy H’ of S1 or of SD that sits as a Skula-closed subspace of X.

When X is first-countable, we can refine Lemma E as follows. A UCO subset (“union of closed and open”) of a topological space is a union of a closed subset and of an open subset. UCO subsets were mentioned in the March 2019 post on countably presented locales, or in the August 2019 post on sober subspaces and the Skula topology, or in the September 2025 post on compactly Choquet-complete spaces. A Π02 subset is a countable intersection of UCO subsets. Every Π02 subset is Skula-closed; in fact the Skula-closed subsets are the intersections of UCO subsets, not necessarily just countably many of them. The following is Theorem 3.4 of [3].

Lemma E’. In the Setting, and if X is also first-countable, then any countably infinite subset A of C0 such that cl (A) = C0 is Π02 in X. In particular, H is Π02 in X, and the subspaces H’ found in Lemma C or in Lemma D are Π02 in X.

Proof. We claim that:

- Every open subset of X, every closed subset of X is UCO, hence Π02.

- Every one-element set {x} is Π02. Since X is first-countable, x has a countable base of open neighborhoods (Un)n ∈ N, hence {x} = ↓x ⋂ ↑x = ↓x ⋂ ∩n ∈ N Un, which is Π02.

- Every finite union of Π02 subsets is Π02. It suffices to observe that finite unions of UCO subsets are UCO subsets, and to distribute countable intersections over finite unions.

- Every compact saturated subset Q is Π02. Let (Uxn)n ∈ N be a countable base of open neighborhoods of each point x of Q. Following Exercise 4.7.14 in the book, we will assume that they form a descending sequence Ux0 ⊇ Ux1 ⊇ … ⊇ Uxn ⊇ …; the fact that they form a base of open neighborhoods means that every open neighborhood of x contains some Uxn.

For every n ∈ N, the sets Uxn where x varies over Q form an open cover of Q. We extract a finite subcover (Uxn)x ∈ An (where each set An is a finite subset of Q), and we write Vn for ∪x ∈ An Uxn.

Then Q ⊆ Vn, and we claim that Q = ∩n ∈ N Vn; this will show the claim. In fact , this will even show that Q is Gδ, in other words, a countable intersection of open sets.

Since Q is saturated, it is equal to the intersection of its open neighborhoods, so it suffices to show that every open neighborhood V of Q contains some Vn. We fix V, and for every point x of Q, we find an open neighborhood Uxnx in the base (Uxn)n ∈ N of open neighborhoods of x that is included in V—this is by definition of a base of open neighborhoods. Since Q is compact, a finite number of such open neighborhoods Uxnx cover Q. We take n larger than or equal to all the finitely many numbers nx thus obtained, and then Vn ⊆ V.

We now proceed just like in the proof of Lemma E, replacing “Skula-closed” by “Π02” everywhere: An ≝ {y0, y1, …, yn} ∪ Qn is now Π02 for every n ∈ N, so A = (∩n ∈ N An) ⋂ C0 is Π02, too. ☐

We turn to the converse: showing that an ω-well-filtered space cannot contain any Skula-closed subspace homeomorphic to S1 or to SD.. This requires a detour through some properties of ω-well-filtered spaces and ω-Rudin sets.

Skula-closed subspaces of ω-well-filtered spaces

The characteristic feature of the set C0 we have built and studied in previous sections is that it is a minimal closed set that intersects every element Qn from a descending sequence of compact saturated subsets. Such sets are very much related to the following notion, due to Xiaoquan Xu, Chong Shen, Xiaoyong Xi and Dongsheng Zhao [4, Definition 5.1].

Definition. A closed subset C of a topological space X is ω-Rudin if and only if there is a descending sequence Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … of compact saturated subsets of X such that C is a minimal closed set that intersects every Qn.

In general, an ω-Rudin subset is a subset whose closure is ω-Rudin, but we will not need that generality. The notion originally stems from the topological Rudin lemma, which we have seen in the February 2021 post.

The following is Corollary 6.11, item (2) in [4]. We note that every set of the form ↓x is closed (since it is the closure of x) and ω-Rudin: take Qn ≝ ↑x for every n ∈ N, then Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … is a descending sequence of compact saturated subsets of X that all intersect ↓x, and every closed set C that intersects every Qn must contain x, hence be a superset of ↓x, which shows the minimality of ↓x.

Proposition F. Let X be a topological space. Then X is ω-well-filtered if and only if every ω-Rudin closed subset of X is of the form ↓x for some point x of X.

Proof. We show that the negations of the given properties are equivalent, namely that X is not ω-well-filtered if and only if there is an ω-Rudin closed subset of X that is not of the form ↓x for any point x of X.

If X is not ω-well-filtered, then we reuse the Setting. By Lemmas C and D, there is a subspace H’ of X that is homeomorphic to S1 or to SD and such that cl (H’) = C0, a minimal closed set that intersects every Qn, and such that C0 is disjoint from ∩n ∈ N Qn. In particular, C0 is closed and ω-Rudin, but not of the form ↓x for any point x of X.

Conversely, let us assume that we can find an ω-Rudin closed subset C of X that is not of the form ↓x for any point x of X. By definition of an ω-Rudin set, there is a descending sequence Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … of compact saturated subsets of X such that C is a minimal closed set that intersects every Qn. Let U be the complement of C in X. Then no Qn is included in U.

If ∩n ∈ N Qn and C had a non-empty intersection, then we could pick a point x in that intersection, and then ↓x would be a closed subset of X that intersects every Qn. This is impossible since ↓x is a proper subset of C, and since C is minimal. Therefore ∩n ∈ N Qn and C are disjoint. In other words, ∩n ∈ N Qn is included in U. Since no Qn is included in U, X is not ω-well-filtered. ☐

Proposition G. Every Skula-closed subspace of an ω-well-filtered space is ω-well-filtered.

Proof. The argument is buried inside the proof of [3, Theorem 3.3]. Let X be a Skula-closed subspace of an ω-well-filtered space Y. In order to show that X is ω-well-filtered, we rely on Proposition F: we consider an arbitrary ω-Rudin closed subset C of X, and we wish to prove that C = ↓x for some point x of X. By definition, there is a descending sequence K0 ⊇ K1 ⊇ … ⊇ Kn ⊇ … of compact saturated subsets of X such that C is a minimal closed subset of X that intersects every Kn.

Let us write clY for closure in Y, ↑Y for upward closure in Y and ↓Y for downward closure in Y. (We keep ↓ for downward closure in X.)

Let C’ ≝ clY (C). We claim that C’ is ω-Rudin in Y.

- First, we note that C’ ⋂ X = C. The inclusion C ⊆ C’ ⋂ X is clear. Conversely, since C is closed in X, we can write C as C” ⋂ X for some closed subset C” of Y. Then C ⊆ C”, and since C” is closed in Y, clY (C) ⊆ C”, in other words C’ ⊆ C”. Then C’ ⋂ X ⊆ C” ⋂ X = C.

- It is easy to see that a compact subset of X is also compact in Y, so every Kn is compact in X. We let Qn ≝ ↑YKn for every n ∈ N, so Qn is compact saturated in Y. Also, Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … is a descending sequence of compact saturated subsets of Y, and Qn ⋂ X = Kn for every n ∈ N: the latter is because Kn is saturated in X, and the specialization preordering of X is the restriction of that of Y.

- Since C’ contains C and Qn contains Kn for every n ∈ N, and since C intersects every Kn, C’ intersects every Qn.

- Now let us imagine a closed subset C” of Y, included in C’ and which still intersects every Qn. Then C” ⋂ X is closed in X, intersects every Kn, and is included in C’ ⋂ X, which is equal to C, as we have seen above. By the minimality property of C, C” ⋂ X = C. In particular, C” contains C, and since C” is closed in Y, it must also contain clY (C), namely C’. But C” is included in C’, so C” = C’.

This shows that C’ is a minimal closed subset of Y that intersects every Qn. Hence C’ is ω-Rudin in Y, as promised.

Because Y is ω-well-filtered, by Proposition F there is a point y of Y such that C’ = ↓Yy. Every Skula-open neighborhood O of y contains an intersection U ⋂ C” of an open subset U of Y and of a closed subset C” of Y, which both contain y, by definition of the Skula topology. This intersection contains the smaller intersection U ⋂ ↓Yy, which is also Skula-open. We finally use the fact that X is Skula-closed in Y: if y were not in X, then we could take the complement of X in Y for the Skula-open set O, showing that there would be an open neighborhood U of y in Y such that U ⋂ ↓Yy is included in O, namely disjoint from X. But C’ = ↓Yy, so that would entail that U ⋂ C’ ⋂ X = ∅, equivalently that U ⋂ C = ∅; meanwhile, U intersects C’ = ↓Yy (at y), and C’ = clY (C), so U must intersect C: contradiction.

Therefore y is in X. We have C = C’ ⋂ X = ↓Yy ⋂ X, and since y is in X, the latter is just ↓y. ☐

The main theorem

We finally arrive at the main theorem I wanted to come to [3, Theorem 3.3].

Theorem H (Miao-Jia-Shen-Li). A T0 topological space X is ω-well-filtered if and only if it does not contain any Skula-closed subspace homeomorphic to S1 or to SD.

A first-countable T0 topological space X is ω-well-filtered if and only if it does not contain any Π02 subspace homeomorphic to S1 or to SD.

Proof. If X is ω-well-filtered, then every Skula-closed subspace Y (in particular every Π02 subspace) of X is itself ω-well-filtered. At the beginning of this post, we have seen that S1 and SD are not ω-well-filtered. Hence X does not contain any Skula-closed subspace homeomorphic to S1 or to SD.

Conversely, if X is not ω-well-filtered and T0 (resp. and first-countable) , we have seen in Lemmas C, D and E (resp. and E’) that there is a homeomorphic copy H’ of S1 or of SD that sits as a Skula-closed (resp. Π02) subspace of X. ☐

I have the hope that this could be a first step in eventually explaining de Brecht’s results on quasi-Polish spaces in [1]. We will see! In the meantime, I would like to conclude with an application to first-countable sober spaces.

First-countable sober spaces, first-countable ω-well-filtered spaces

In the first-countable case, we obtain a bit more, and we can characterize sobriety, not just ω-well-filteredness. This is due to Xiaoquan Xu, Chong Shen, Xiaoyong Xi, and Dongsheng Zhao [4, Theorem 4.1].

Let me remind you, from Section 8.2.1 in the book, that an irreducible closed subset of a space X is a closed subset C that is non-empty and such that if C is included in a union of two closed sets, then it must be included in one of them already. Equivalently, C is non-empty and given any two open sets U and V that C intersects, U ⋂ V also intersects C. Yet another equivalent definition is: C is irreducible if and only if for every finite family of open subsets of X that intersect C, their intersection also intersects C.

Every subset of the form ↓x is irreducible closed. A quasi-sober space is a space in which every irreducible closed is of the form ↓x for some point x, and a sober space is a T0 quasi-sober space.

We rely on the following [4, Theorem 4.1].

Lemma I. In a first-countable ω-well-filtered topological space X, every irreducible closed subset C is directed in the specialization preordering.

Proof. Let (Uxn)n ∈ N be a countable base of open neighborhoods of each point x of C. Following Exercise 4.7.14 in the book, we will assume that they form a descending sequence Ux0 ⊇ Ux1 ⊇ … ⊇ Uxn ⊇ …; the fact that they form a base of open neighborhoods means that every open neighborhood of x contains some Uxn. (Yes, I have already said all this earlier in this post.)

C is non-empty, and it remains to show that given any two points x and y of C, there is a point z above x and y in C, in other words that ↑x ⋂ ↑y ⋂ C is non-empty.

Since x and y are in C, C intersects Ux0 and Uy0, and because C is irreducible, C must then intersect Ux0 ⋂ Uy0. Let z0 be a point in the intersection Ux0 ⋂ Uy0 ⋂ C. We now have three points in C, x, y and z0. Then C intersects Ux1, Uy1 and Uz01, so C intersects their intersection: let z1 be a point in the intersection Ux1 ⋂ Uy1 ⋂ Uz01 ⋂ C. We now have four points in C, x, y, z0 and z1. Then C intersects Ux2, Uy2, Uz02 and Uz12, so C intersects their intersection, and we then pick a point z2 be a point in the intersection Ux2 ⋂ Uy2 ⋂ Uz02 ⋂ Uz12 ⋂ C. We proceed this way forever, and we obtain points zk in Uxk ⋂ Uyk ⋂ Uz0k ⋂ … ⋂ Uzk–1k ⋂ C for every k ∈ N.

For every n ∈ N, let Kn ≝ {zn, zn+1, …}. We claim that Kn is compact. Let (Vi)i ∈ I be an open cover of Kn. Then zn is in Vi for some i ∈ I. By definition of (Uznm)m ∈ N as a base of open neighborhoods of zn, there is an index m ∈ N such that Uznm ⊆ Vi. For every k≥m, zk is in Uxk ⋂ Uyk ⋂ Uz0k ⋂ … ⋂ Uzk–1k ⋂ C, hence in Uznk. Since (Uznm)m ∈ N forms a descending sequence and k≥m, Uznk is included in Uznm, hence in Vi: therefore zk ∈ Vi for every k≥m. The remaining finitely many elements z0, z1, …, zk–1 are covered by finitely many sets Vj, j ∈ I, yielding a finite subcover of Kn.

Since Kn is compact, Qn ≝ ↑Kn is compact saturated. It is clear that Q0 ⊇ Q1 ⊇ … ⊇ Qn ⊇ … Let U be the complement of C. If ∩n ∈ N Qn were included in U, then some Qn would be included in U, since we have assumed X ω-well-filtered; but this is impossible, since zn ∈ Kn ⊆ Qn and zn is in C, hence not in U. Therefore ∩n ∈ N Qn is not included in U; equivalently, ∩n ∈ N Qn intersects C.

We pick a point z in the intersection ∩n ∈ N Qn ⋂ C. For every n ∈ N, z is in Qn, and is therefore above some point zk with k≥n. We recall that zk is in Uxk ⋂ Uyk ⋂ Uz0k ⋂ … ⋂ Uzk–1k ⋂ C, in particular in Uxk ⋂ Uyk. Since (Uxk)k ∈ N forms a descending sequence and k≥n, zk is also in Uxn, and since Uxn is upwards-closed and zk≤z, z is in Uxn. Similarly, z is in Uyn. This holds for every n ∈ N, so z ∈ ∩n ∈ N Uxn = ↑x and z ∈ ∩n ∈ N Uyn = ↑y. Since z is also in C, we have found the desired point of C above x and y. ☐

Every sober space is a monotone convergence space, namely a space that is a dcpo in its specialization ordering, and whose topology is coarser than the Scott topology of the specialization ordering (Proposition 8.2.34 in the book). This admits the following generalization to well-filtered spaces.

Lemma I. Every well-filtered T0 space X is a monotone convergence space.

Proof. Let (xi)i ∈ I be a directed family in X. For each i ∈ I, let Qi ≝ ↑xi. Then (Qi)i ∈ I is a filtered family of compact saturated subsets. Let Q be its intersection. Let also C ≝ cl ({xi | i ∈ I}) and U be the complement of C. If Q ⊆ U, then the fact that X is well-filtered implies that some Qi is included in U; but that would imply xi ∈ U, which is impossible. Therefore Q is not included in U, hence intersects C. Let x be a point in the intersection. Since x ∈ Q = ∩i ∈ I Qi = ∩i ∈ I ↑xi, x is an upper bound of (xi)i ∈ I. Given any other upper bound y, every open neighborhood U of x intersects C, hence {xi | i ∈ I}, so U contains some xi; because U is upwards-closed and xi≤y, y is in U. We have just shown that every open neighborhood of x contains y, so x≤y. Since y is an arbitrary upper bound of (xi)i ∈ I, x is the least upper bound of (xi)i ∈ I.

It remains to show that every open subset U of X is Scott-open with respect to the specialization ordering ≤. U is upwards-closed, and given any directed family (xi)i ∈ I, with its supremum x in U, we claim that some xi is in U. The point x is built as in the previous paragraph, and we have seen that any open neighborhood U of x intersects C, hence {xi | i ∈ I}, so U contains some xi; this concludes the proof. ☐

We conclude with the following, which is Corollary 3.13 of [2] or Theorem 4.2 of [4].

Theorem J. For a first-countable T0 topological space X, the following are equivalent:

- X is sober;

- X is well-filtered;

- X is an ω-well-filtered monotone convergence space;

- X is a monotone convergence space and does not contain any Π02 subspace homeomorphic to S1 or to SD.

Proof. We already know that 1 ⇒ 2. 2 entails that X is ω-well-filtered, and a dcpo by Lemma I, so 2 ⇒ 3. 3 is equivalent to 4 by Theorem I.

Finally, we show that 3 ⇒ 1. Let X be ω-well-filtered, first-countable, T0, and a monotone convergence space. By Lemma I, every irreducible closed subset C of X is directed. Since X is a monotone convergence space, C has a least upper bound x, and C is Scott-closed, so x ∈ C. In particular, ↓x ⊆ C. Since x is an upper bound of C, C ⊆ ↓x. Therefore C = ↓x and hence X is sober. ☐

- Matthew de Brecht. A generalization of a theorem of Hurewicz for quasi-Polish spaces. Logical Methods in Computer Science, 14(1:13)2018, pages 1–18, 2018; arXiv report 1711.09326.

- Qingguo Li, Mengjie Jin, Hualin Miao, and Siheng Chen. On some results related to sober spaces. Acta Mathematica Scientia 43, pages 1477-1490, 2023.

- Hualin Miao, Xiaodong Jia, Ao Shen, and Qingguo Li. ω-well-filtered spaces revisited. Houston Journal of Mathematics 50(2), pages 477-495, 2024.

- Xiaoquan Xu, Chong Shen, Xiaoyong Xi, and Dongsheng Zhao, First countability, ω-well-filtered spaces and reflections, Topology and its Applications 279, 107255, 2020.

— Jean Goubault-Larrecq (February 20th, 2026)